Fun with Statcast: Atlanta's lopsided use of shifts on defense

The Atlanta Braves are on both ends of infield positioning under the current rules...but it's absolutely working for them.

(A fun one for you today - I was poking around in Statcast for a newsletter I’m working on and found something intriguing that I thought I’d share. Let me know if you enjoy things like this!)

Major League Baseball had enough.

In September of 2022, citing a lack of “on-field action”, the league office announced restrictions on defensive shifts by infielders. No longer could you station a third baseman in shallow right field for a left-handed hitter, or have three infielders on the dirt on the first base side of the diamond (unless one of the extra players is an outfielder).

No, going forward, teams would be required all infielders to have both feet on the dirt with two completely on each side of second base. The league even made a helpful graphic to illustrate the new rules on positioning.

Accordingly, Atlanta’s usage of shifts changed…but probably not in the ways you expected.

Let’s talk about it.

What the Braves did before the ban

Conveniently, Statcast began building leaderboards for defensive positioning for the 2022 season, quantifying how often teams shifted defenders in response to the hitters at the plate.

Atlanta was roughly middle of the pack in defensive shifts, coming in at 18th at 29.6% of plate appearances featuring shifts. It wasn’t quite an even split between lefties and righties, with southpaws seeing a shift on 38.6% of plate appearances and righties on 22.8%.

That shift percentage against lefthanders was 29th out of 30 teams - only Colorado at 27.8% shifted less often in those situations, while the 2022 Houston Astros did it over 80% of the time to pace the league.

But the Braves made up for it with righthanders - that 22.8% mark ranked 8th-most in all of baseball. It worked, too. Atlanta’s infield OAA was third-best in baseball at +17, with the Braves being fifth-best against righties (+11, tied with Houston) and 7th against lefties (+7)

The inflection point was Ron Washington’s departure

After losing Dansby Swanson to the Chicago Cubs and switching over to Orlando Arcia as the primary defensive shortstop, the Braves kept doing the same things on defense with their defensive “shades” while the rest of the league recalibrated - their 24.3% mark against righties was #1 in baseball, while lefties saw a defensive shade on 42.1% of at-bats. With the league acclimatizing to new restrictions on infielder movement, that roughly similar percentage rose from 29th to 18th in baseball.

The results cratered, though. Atlanta’s infield was just 25th in baseball at -17, putting up negative marks against both righties (-11) and lefties (-5).

And then Ron Washington left to go manage the Los Angeles Angels.

More extremes with their defensive positioning

Under new infield coach Walt Weiss and coming off of a poor defensive year, Atlanta hewed more to the league’s thinking on defensive shades, cutting down how much they did it against righties (7.6%) and increasing how much they did it against lefties (49.9%).

Despite all of the injuries last season, the change in approach worked - Atlanta was 14th in baseball at +7, putting up a +8 mark against righties and an even 0 against lefties.1

The improvement on defense, combined with the addition of an elite glove like Nick Allen, have caused the Braves to double down on their strategy this season.

In 2025, the Braves are a top-five defense in shifting against southpaws at 72.2% while tying with the Nationals for the least righty shifts at 0.3%.2 Both teams have shifted just three times in over 960 plate appearances against righties but have 548 in 759 PAs against lefties.

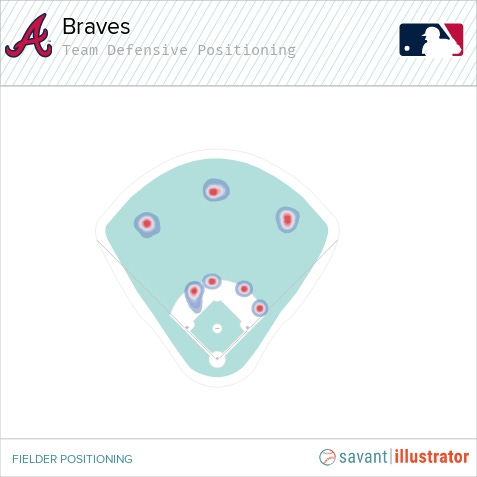

And as you’ll see by the heatmap of their defensive positioning in those lefty shifts, the biggest adjustment comes from Austin Riley.

Against lefties, Riley’s essentially playing as the shortstop, with Allen stationed up the middle as far over as he’s legally allowed to go.

Overall, Riley’s playing a deeper third base, 121 feet from the plate, while having a -31° angle from the bag, being farther away from the third-base line.3 Consequently, he’s also putting up a career-high +1 OAA mark so far this season, a testament to the defensive and conditioning work he did over the offseason.

As a whole, Atlanta’s defensive adjustments are noticeable in the OAA improvements - Atlanta’s +16 mark is 2nd in baseball, with Allen and Riley on the left side fueling the team’s +12 mark against righties. Ozzie’s range has improved this season, per Statcast, and it’s because the team’s able to position him farther towards first base against lefties thanks to Allen’s improved range over Orlando Arcia up the middle.

Does the shift even matter?

Anecdotally, I’d argue it absolutely does, but what do the numbers tell us?

Per my old colleague Tom Verducci at Sports Illustrated, the best teams are just hitting the ball over the infielders anyway - each of the last five World Series winners was somewhere between the best team in baseball and the fifth-best team in baseball that season at avoiding ground balls, which have an average batting average of just .245 across that span.

(For completeness, line drives produced a .636, fly balls a .268, and pop-ups a .015 average.)

But for specifically the Braves, I looked at overall batting average versus lefties in each of those five seasons:

2021: .249

2022: .243

2023: .270

2024: .239

2025: .242

I think it’s clear that this defensive change absolutely has proven to give the team its best performance against lefties, judging by the overall batting average allowed.

This holds up if you look at wOBA, as well:

2021: .326

2022: .321

2023: .357

2024: .306

2025: .308

While there are some other variables here - different pitchers can impact the ratio of fly balls to grounders, etc. - it’s pretty telling that the team’s two best defensive performances have come after losing Ron Washington. He built the foundation, but these guys take pride in their defense and have continued to work to improve their glove work.

Some better positioning doesn’t hurt, either.

The overall number is calculated separately from the numbers for lefties and righties, so rounding and things like that sometimes result in a one-digit difference between the overall score and the combined score of lefties + righties

Although Atlanta has 20 less PAs, 984 to 961, so they’re technically 29th and Washington’s 30th.

The “angle from the bag” denotes how deep the player is set up in the infield. If he’s exactly in line with the bag, essentially standing in the basepath, it’s 0°. In this case, Riley’s average starting point is negative 31 degrees, meaning 31 degrees behind the basepath as measured from the base.

Working on your day off, eh? Thanks, Lindsay