No team hits into loud outs like the Atlanta Braves

No team hits it harder for outs, and no stat sums up the Braves’ frustrations quite like this one

The roster-building philosophy of the Atlanta Braves can be distilled to one thing: find guys who can knock the absolute heck out of the ball.

But hitting it 110 mph doesn’t help much if there’s a glove in the way.

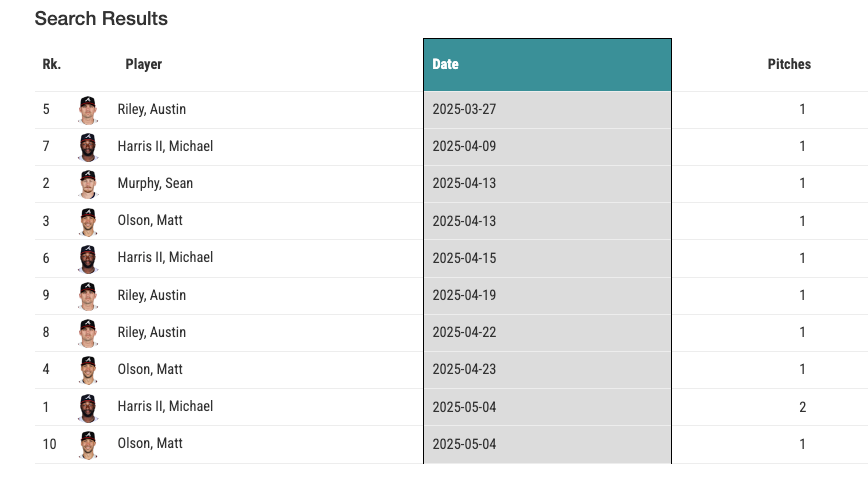

As of the end of their series with the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Braves led MLB with 11 batted balls at 110+ mph that went for outs. They’re the only team in double digits—the next closest are the Pirates and Mariners, with eight apiece.

By request from a paid subscriber to the newsletter, let’s talk about it.

It’s mostly the guys you expect

Given that this is a measure that’s heavily influenced by how hard you can swing the bat and playing time, the guys who have fallen victim to this misfortune are everyday players who can absolutely mash a baseball. Four of the team’s top five players in average exit velocity on the year are the four players who make up this list: Matt Olson, Austin Riley, Sean Murphy, and Michael Harris II.

Designated hitter Marcell Ozuna, despite having the 2nd-highest average exit velocity on the roster, isn’t included in here by virtue of luck.

I’ll admit, Harris is one of the more surprising ones to be on this link - we talked just yesterday about how he’s not swinging as hard this year, but not only does he have multiple 110+ mph outs, he leads the entire team with four of them.

Let’s break down the different types of Braves loud outs, which we’re hereafter going to call CHOP outs - Crushed Hard, but Out Predictably.

Five absolutely smoked grounders

Five of Atlanta’s league-leading eleven CHOP outs were absolutely smoked, but on the ground that were somewhat easily fielded for outs.

Nobody’s done this more than once, except for Harris, and thankfully, it almost always resulted in just one out rather than multiple.

Michael Harris had the first CHOP grounder of the year in the Philly series, a chopper that Trea Turner corralled and subsequently beat him by a half step.

The next two were from the same game, with Matt Olson getting robbed by a good pick by Tampa Bay second baseman Coco Montes in the 2nd inning…

…followed by Sean Murphy hitting into a double play in the 9th, one that required a bit of quick-twitch work from shortstop Taylor Walls.

The last two groundouts (and the inspiration for this piece) were from the same player in the same game: Michael Harris in the finale versus the Dodgers.

First, he sent one up the middle in the 3rd, off of pitcher Dustin May and to second baseman Kiké Hernandez.

Then he cut the pitcher out of it and just gave one directly to Kiké in the 6th inning:

Believe it or not, this game had a third CHOP out, which came prior to Harris’ groundout in the 3rd inning. You see why I wanted to go back and look at this, right?

The lineouts came in bunches

I sorted the above statcast results by date, but what that view doesn’t show is that the Braves opened the season with a CHOP lineout, had three CHOP groundouts in a row, and then five consecutive CHOP lineouts before their next two groundouts (both on Sunday versus the Dodgers).

Austin Riley got the season started with one in the season opener versus the Padres, a liner in which Brandon Lockridge didn’t have to move that far to corral. I think Statcast rated this a one-star catch.

The defensive actions there are repeated in the next several: Michael Harris laced one right to right fielder Addison Barger in Toronto, although he did need to retreat to the warning track to bring it in:

Austin Riley gave Harrison Bader a bit of a challenge, but ultimately not too much of one:

But Lars Nootbaar did need to get a good jump to keep this one from either dropping in front of him for a single or getting past him for an extra base hit:

The final one I have, the first of three in the series finale against the Dodgers on Sunday, was also the only line drive that was caught for an out by an infielder. Once again, it was Kiké Hernandez, this time robbing Matt Olson:

Anything we can take away from these?

Honestly, I don’t think so. It’s eleven outs out of 837 batted balls this year for the Braves.

There are some trends, though, which probably aren’t statistically significant but are still interesting.

Matt Olson had the three hardest-hit balls (113.8, 113.5, and 112.2) and the worst luck, hitting an infield line out when his batted ball was too low of a launch angle to get caught by an outfielder - it would have been a hit if not for Kiké.

The Braves lost only one of the two games in which they had more than one hard-hit out. In the Olson clip for the Tampa Bay loss on 4/13, you can hear Brandon Gaudin mention after the putout how unlucky Atlanta was with their batted balls in that contest. Atlanta had seven hard-hit balls, all at 99.9 mph or harder, and got a grand total of one single out of it, losing 8-3.

And really, the overall story here is bad luck. All but one of those batted balls (the Michael Harris groundout to Trea Turner) had expected batting averages of at least .522, with four of them at .790 or better. And they were all outs.

This kind of thing normalizes over a full season - last year, the Braves had an actual batting average of .243 and an expected batting average of .244.

But in a small sample, like eleven batted balls, it’s definitely frustrating.

The Braves aren’t broken—they’re just cursed by leather. Eventually, those CHOPs (Crushed Hardballs, Out Painfully) will turn into runs. Until then, Atlanta leads the league in the loudest outs money can buy.

Does the stats take into account the defensive shift that teams employ against our hitters? Or is that something which normalises as well, because every team runs different defensive alignments? Is luck purely the defining factor here on CHOP outs?